Battlefield 2042 critique – DICE’s enchanting FPS formula is stretched too thinly

2042 debuts as the worst Battlefield in a while, while Portal offers some cool new tools and the franchise at its finest.

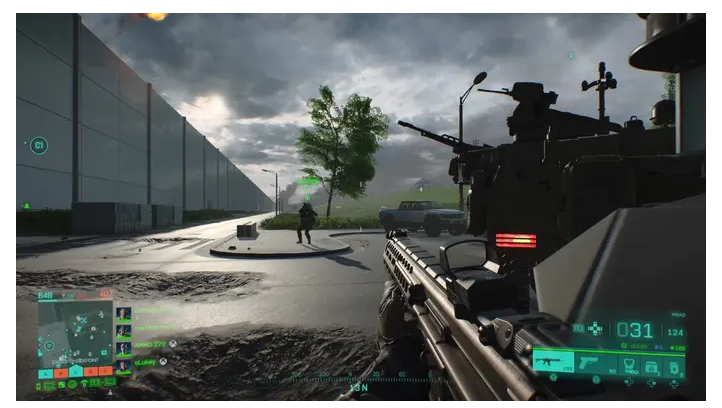

Really, there isn’t a shooter like Battlefield. Indeed, no other series compares to Battlefield when it comes to delivering anarchy on such an exhilaratingly large scale. The appeal of DICE’s expansive squad-based first-person shooter, which is more GTA than Call of Duty, has always been in the way its players engage with the many toys in its sandbox, hurling them at one another like well-mannered kids. Frequently, the outcomes are both impressive and amusing.

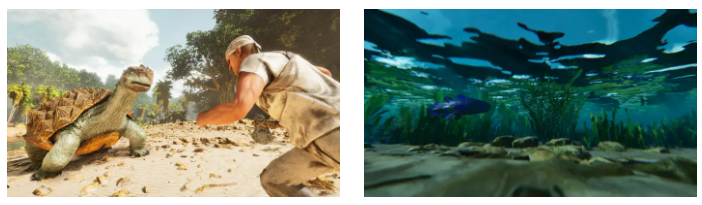

I just played Battlefield 2042, and if you know where to search, you can still find those magical moments. I’ve climbed 60 floors to the top of a building with my squad, packed inside an elevator, and then waited silently for the doors to open before letting loose and eliminating two opposing teams. After securing the point, I parachute down to secure another one just to be safe. I’ve run through sandstorms, seen cars slam as debris rips through the atmosphere, only to emerge from one to find a burning aircraft loudly spiraling at my face. The enormous map around me whirled like a horrific catherine wheel as I laughed and stared in shock.

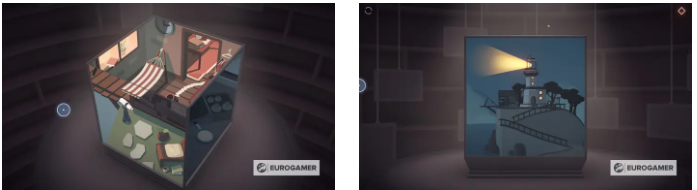

In a sense, Battlefield 2042 is a celebration of all that. Portal, a mode that lets users explore the sandboxes individually while panning back, is a key feature of its three-part package. These are vintage maps that have been taken from Battlefield 1942, Battlefield 3, and Bad Company 2, along with movesets and rules that are unique to each game. You may mix and combine the games to your heart’s content, such as utilizing Battlefield 3’s toybox for Conquest at Noshahr Canals or Bad Company 2’s tools and rules for Rush at Arica Harbor. Alternatively, you can stick to the tried-and-true games.

It brings back more feelings than simply a nostalgic thrill to play with these beloved vintage toys that have been polished to a glossy contemporary finish. It serves as a reminder of the Battlefield formula’s power, the reason so many players stick with the game through its sometimes difficult moments, and the reason the community has always remained so strong. You can see just how much the series’ formula has altered when Battlefield 2042 is placed next to All-Out Warfare, the mode that houses both the game’s new set of toys and tricks and its five enormous new maps that handle 128 players in both Conquest and Breakthrough variants. And quite a few of those modifications are very peculiar.

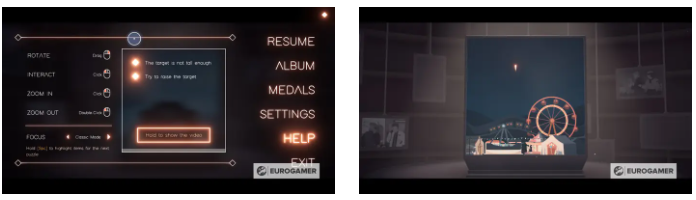

The greatest surprise is perhaps how little of an effect the new Specialists—hero-like characters that replace the previous class structure while bringing their own special powers to the battlefield—have in the long run. Based mostly on the current classes, they provide some interesting twists. As a support player, I like Casper’s recon possibilities and Falck’s long-range healing, but overall, I feel that they detract from rather than improve squad balance. Though the amount of options you have is great, loadouts quickly get standardized to the point that every build seems quite similar, especially considering how few weapons are available at start.

The system might still need some refining, but for now it seems like a collection of imprecise design choices. Even after more than 20 hours playing Battlefield 2042, the scoreboard’s disappearance is still a bit of a sore spot. It’s antithetical to the rivalry and camaraderie you develop when you spend an evening in any given server, seeing the same usernames at the end of your sights or being steamrolled by the same close-knit squad. I understand that the purpose is to promote teamwork and discourage lone wolves. Although again reasonable, the absence of voice communication in-game appears to go against the spirit of cooperation required to appreciate a game like Battlefield.

The maps in All-Out Warfare sometimes appear to work against having a fun Battlefield experience. Undoubtedly, Battlefield 2042’s 128 players make it competitive with other major Battle Royale games in terms of marketing points. However, the game’s expansive areas merely compound the issues that new players often have with the series: they feel like they’re constantly running from one place to another with little action in between, only to be sniped cleanly as soon as they reach their goal and forced to run endlessly again.

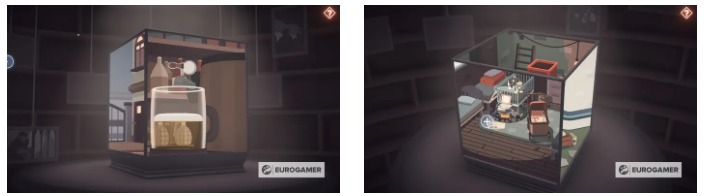

It helps, of course, to be squadded up by default and to be able to airdrop vehicles (one of the most crushingly powerful additions to Battlefield in years, a genuinely deadly hovercraft that can lollop over whole mobs and even climb buildings). All-Out Warfare has several amazing capabilities, such the cross menu that allows you to quickly change the sights and attachments on your weapon to fit the circumstance. After a patch fixed some of the issues with the early launch experience, it feels and runs rather well. Despite the near-future scenario giving it a relatively bland appearance, it is still capable of producing some really amazing spectacles.

It’s unfortunate that it’s now so little distributed. The faster-paced combat on the vintage maps in Portal mode and the slower-paced action in All-Out Warfare are quite different from one another. The squad-based Hazard Zone game, which is modeled after Escape From Tarkov and pits teams against AI enemies as they battle to recover and extract data packets, is, in fact, the most enjoyable way to use the current toolkit. When everything works together, it’s a stressful and really fun game, but I’m not convinced it presently has enough replay value to lure people away from any of its rivals or be a long-term contender.

To be honest, I’m not sure whether Battlefield 2042 will win over series newbies just yet. While Hazard Zone is entertaining, it’s a little restricted, and All-Out Warfare has too many bugs at launch to be worth the money. That brings us to Portal, where the classic Battlefield magic is, evidently, at its peak. However, there’s a worry that the player base may become more dispersed the more user-made games and modifications are added. This is a game that is begging for players, since there are now 128 spaces available in several of its modes, and it already seems like some of them won’t last. I’ve found some unsettlingly lonely matches in a game that offers a publicly accessible 10-hour trial, which just makes the desolation of such landscapes worse.

Not to mention the issues and malfunctions that persist regularly even after the first patch was applied. Unfortunately, they’re part of the landscape when it comes to a new Battlefield; seasoned gamers will be used to them, but beginners will probably find them off-putting. After the first updates, there’s a good possibility things will go more smoothly, but with the intense rivalry in the first-person shooter market, it could already be too late. It’s not like Battlefield 2042 is without other issues, however.

Despite its size and scale, Battlefield 2042 seems to be the most jumbled, compromised, and perplexing game in the franchise so far. It has more existential issues than Battlefield 4, which had a similarly problematic launch. However, there’s a possibility DICE can pull off what it did so well with Battlefield 4 and Battlefront 2, which both had their share of controversy. There are enough instances of the classic magic in Battlefield 2042, along with some clever but raw new concepts, to imply that the game still has hope for the future with more refinement and concentration. For the time being, however, consider this to be just another somewhat flawed Battlefield launch—at least, one that has been flawed in novel and intriguing ways.