One genre where side projects often threaten to take center stage is role-playing role games. A lot of older examples are structured around a more deliberate conflict between primary and supporting material than, say, modern open world games, where everything is always accessible. Consider how Tetra Master in Final Fantasy VIII forced you to put the story on pause for days at a time, or the perilously close to Sokoban block puzzles seen in the earlier Wild Arms titles. These kinds of areas are where RPG designers sometimes hide their greatest ideas—or, at the very least, their most bizarre ones—from the pressures and limitations of the main production.

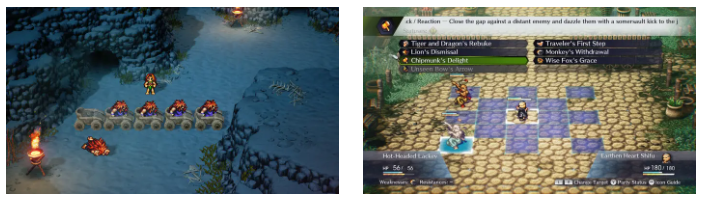

Live A Live, first published in 1994 and remade in the same sprites-meets-polygons manner as Octopath Traveller, is basically Sidequest: The Game, which is something I probably should have realized before comparing it to a Sonic level-select trick. It’s an assortment of loosely connected, one to three-hour stories that take place in various historical and/or fantastical eras, each with a unique and colorful take on what a classic Squaresoft role-playing game should be. Similar to sidequests in conventional single-narrative role-playing games, some chapters are more successful than others, but all are captivating experiments. The overarching, grid-based battle system is worth the roughly 20 hours it will take you to reach the closing credits, despite the stop-start anthology structure.

The nine chapters of the game—seven of which are initially playable—share equipment and leveling systems, but aside from that, each is a unique story with its own protagonist, usually a man, though women mostly appear as helpless victims—party members, a couple of signature mechanics, and a flavorful writing style. One may imagine a far-off prehistoric era when a simian friend and a shaggy Flintstoner accidentally come upon a fugitive girl while flinging excrement at mammoths. This chapter is written in speech bubble emojis, grunts, and other lewd gestures. Conversely, there’s a Wild West chapter with a Man Without a Name—that is, a Man With An Adaptable Name—who joins forces with his adversary to protect a frontier village from bandits. With a chewy, saloon-bar narrative, this feature-length episode revolves on a single set piece puzzle: equip the townspeople with traps to kill as many outlaws as possible before to the pivotal clash.

The humorous benefit of Live A Live’s anthology style is that each of the parts doesn’t have to be flawless. The game’s fascination stems from both its sheer novelty value and the way the development team attempts to rework the same elements to suit a fresh storyline. For example, the imperial China chapter, when an old martial arts teacher puts his three followers through training exercises before facing off against a local thug, didn’t really appeal to me. Though you’re free to choose your favorites, there simply isn’t enough time for such mentor-student bonds to develop.

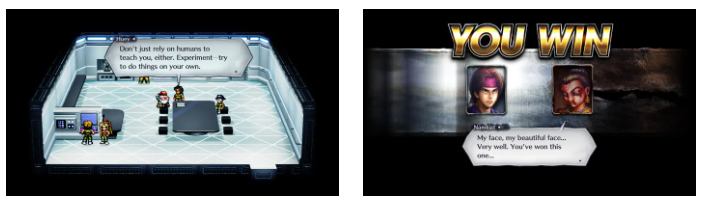

The far-future level, in which you take control of a sentient robot aboard a spacecraft carrying an extraterrestrial creature, also didn’t really appeal to me. Here, the only fighting occurs inside a different videogame in the ship’s recreation area; apart from a few games of hide-and-seek, you’ll be trundling between elevators chasing a crazy star-faring soap drama for the most of the time. Nevertheless, I couldn’t help but applaud the developers—who wouldn’t want to see the people who brought us Dragon Quest try their hand at an Alien or a kung fu epic? In any event, the challenge is designed so that you may complete the chapters in any sequence, and you can easily jump between them using a single save file if you find yourself losing interest.

Certain chapters have a humor-heavy tone. The current era, which is equivalent to the early 1990s, is a parody of Street Fighter that centers on that one character in multiple turn-based role-playing games who can only acquire new skills by imitating opponents. As a potential world champion, you choose opponents from a menu of coin-operated arcade games, evade, and try to bait them with their sexiest movements before knocking them out. It’s delightfully absurd, but not quite as ridiculous as the near-future segment, which stars—deep breath—an orphan delinquent with telepathic abilities who joins up with a punk biker, a scientist akin to Doc Brown, and a robot powered by a turtle to destroy a technological corporation that turns souls into fuel. The story begins with you robbing a park of clothing and selling takoyaki, and it closes with a mech stomping out a large bird. Along with a lively urban overworld and a number of toilet-based puzzles, you may deploy powers that make people mistake you for their own moms.

In part, I liked this chapter because I was curious about what might happen next. However, the segment on Japan during the Edo era was my absolute favorite. Its subtle brilliance lies in the way it challenges the game’s leveling system. As a shinobi, you invade a stronghold to free a prisoner and assassinate a dark arts-wielding ruler. You are instructed to avoid taking too many casualties, and you will lose out on certain awards if you establish a killing streak. However, if you avoid every confrontation and run away, you will lose all fights that cannot be avoided. Thankfully, it is legal to kill non-human entities like ghosts.

This serves as the foundation for a lengthy social stealth puzzle that plays out like a Hitman mission set in Ashina Castle, Sekiro. The objective is to locate enemies that you are allowed to kill while figuring out how a clockwork playspace with swivel doors, secret chambers you can access with your ears, and some really eerie moments involving puppets and shadows behaves. The Edo segment of Live A Live is the most compelling and should be made into a stand-alone game, in contrast to the one-shot chapters of the present and far future.

The main problem with Live A Live’s anthology structure is that, because each of the initially unlocked time periods needs to be sufficiently accessible to be the player’s first choice, with its own miniature arc of challenge and complexity, the combat doesn’t quite evolve over the course of the first fifteen hours. Thankfully, the two final chapters really up the ante, and the last episode in particular offers a chance to truly test the fighting system by enlisting former heroes from all across the world and sending them into character-themed puzzle dungeons to find their ultimate weapons.

Okay, battle! I should really get around to explaining it to you, isn’t that right? Characters’ action bars fill up when another character moves or acts, which is the basic gameplay mechanic. Square grids are used for battle, and a third of the playspace is occupied by several exquisitely rendered bosses. During a character’s turn, you are free to roam about until an opposing action interrupts it. various patterns of tiles are affected by various attacks and abilities. For example, whereas fancier spells may strike out diagonally, melee movements naturally target nearby tiles. Certain skills change the landscape by adding fire or water to tiles. Some adversaries have a casting period during which they might move aside or launch strikes that throw your character off-balance.

The variety of status effects is a little bit overwhelming; they range from debuffs that prevent specific skills from being used to poison and paralysis. Additionally, enemies may be susceptible to some attack types or resistant to others, albeit this isn’t nearly as powerful as staggering enemies in Octopath Traveler. Although equipment selections may be crucial, you won’t need to spend much time navigating menus in between clashes since characters recover themselves fully in between fights and are automatically leveled up, unlocks, and stat increases. While there are a few spots where fights happen at random, most attackers are visible on the global map and are easily avoided (the shinobi can even blend in with the background so that guards may pass past him).

Live A Live is a project that perfectly embodies Square Enix’s nostalgic approach to retro RPG creation, as well as one of its initial inspirations. These games aren’t only modernized tributes, but rather alternative retro-futures that manage to seem both charming and polished.

When seen as a straight-forward contest between your stats and mine, the fight system is at its worst; when viewed as an oddball cousin of chess, it is at its greatest. It all comes down to how well you comprehend the board and, therefore, the individuals you are dealing with thanks to your AOE powers. For example, the near-future criminal is an enhanced Rook that can shoot mental blasts both horizontally and vertically, which lessens his effectiveness against opponents who move like bishops. You’ll need to keep dancing the shinobi about since he has a couple strong AOE techniques that cover the tile below him and leave terrain effects in his wake.

The kung fu master does not have ranged strikes; instead, he relies heavily on closing the gap and using techniques to push his opponent back a square, much as the wushu legend does. In contrast, the cowboy’s specialty is range and single-tile strikes; in fact, part of the reason he’s less effective in a crowded area during the Wild West segment is to thin down the raiding posse. The most fulfilling bouts in the game develop these fundamental problems into intricate spatial puzzles; they include boss battles where you must eliminate the opposing commander in order to beat the other players. Rather of methodically clearing the rank-and-file, you’ll want to clear the way for these VIPs by destroying formations with knockback abilities and piercing bullets.

Live A Live is a perpetually wacky game with significantly more funny fart jokes than musically insightful philosophical lessons. However, behind it all is a moving, subtly subversive message about fostering relationships between individuals in very disparate locations and eras. The last revelation, which should not be too spoilery, is that every chapter is essentially the same struggle—evil isn’t so much the ultimate foe as it is a poisonous meme that exists outside of linear time and must be repeatedly vanquished.

Therefore, Live A Live is both the ideal project and one of the original inspirations behind Square Enix’s present, melancholic approach to retro RPG development. This approach aims to separate reality into a meta-historical dimension where sparkling 3D lighting effects and cinematic transitions coexist with SNES-brand pixel sprites. These games, as I said in my review of Octopath Traveller, are alternative retro-futures that manage to be both sleek and charming, rather than just contemporary takes on classic themes. They provide an open-ended, speculative picture of gaming history by fusing what was and what is into what could have been, which contrasts well with the tiresome industry language of hardware generations and soon-to-be-baked “cutting edge” technologies. You may infer that it is a sidequest-only view of history.