Back 4 Blood critique – an eccentric yet delightfully addictive horde shooter

I had absolutely no ideas on Back 4 Blood for a significant portion of my first experience with it. This peculiar game is based in part on an extreme kind of nostalgia, particularly affecting anyone who have ever spent even a single day in the late 2000s in the same room as an Xbox 360. The other half is suddenly contemporary, with all cards, advancement, and rewards. everything seems as if the two cancel each other out at first, making everything look too familiar and too recognizable. In cooperative mode, I’m blasting zombies, collecting weaponry, and scouring the advancement system for cards that may come in handy during my next run. Say this in your most dispassionate voice: Alright.

Fortunately, however, it goes beyond that. I can now acknowledge that I was utterly mistaken after spending enough time poking about in the strangely alluring darkness of the game. It’s intriguing to read Back 4 Blood. In some regions, it is strange. It’s excellent! Very nice.

Its system of runs is largely responsible for this. Back 4 Blood, as you may already be aware, is a near spiritual successor to Left 4 Dead. It was created by the original Left 4 Dead studio Turtle Rock, which was formerly known as Valve South during the Left 4 Dead years before being refounded in 2011 by several significant figures, including Chris Ashton, Phil Robb, and Michael Booth. This background is significant. Aside from the overall morbidity of the cooperative gameplay, Left 4 Dead wasn’t actually meant to be played through just once. You go through Back 4 Blood more than once as well, but this time around it’s designed that way.

This is when the framework of the campaign system comes into play—the “run” part. When you start a run, you have a choice of three difficulties that increase rather quickly, from a very casual breeze to complete, apocalyptic destruction. You will need both a strong construct and a strong squad in order to succeed at the medium or upper difficulty levels, which is where the second component of the system comes in.

You will get in-game money supply points for finishing a campaign task with any online allies—though, rather controversially, not if you’re playing alone with bots. Points called “supply lines” may be used to advance along “supply lines,” which are basically skill trees. The advancement awards you with cards, which are highly significant, intriguing, and helpful, or sometimes some horrible, useless cosmetics, like a beanie, which aren’t.

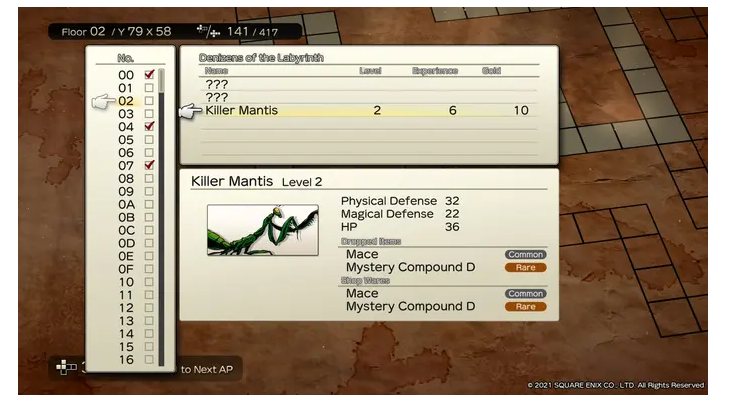

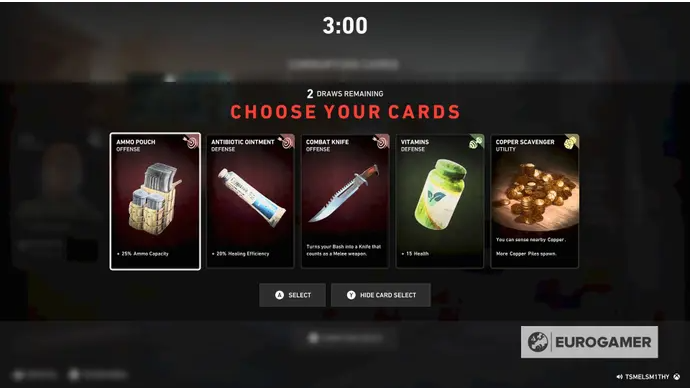

Each of those cards has a distinct ability; they all start out with a simple ability, like +15 health, and grow more specialized and sophisticated over time. For example, one card dramatically enhances reload speed, but at the expense of never being able to aim down sights. To construct a deck, choose fifteen of the cards you have obtained so far. Afterwards, select a deck to utilize for each new run. You choose one card at a time to enter your active construction when five cards from your deck are drawn between each level. It’s important to remember that the cards are drawn in the order that you built them. In addition, the “horde” has a deck of its own, and the level has other random modifiers added to it. At first, the effect seems like a mediocre randomization method, but then all of a sudden it doesn’t.

Because you can’t unlock new cards when playing solo, you’re stuck with an incredibly tame, low-difficulty horde game that changes at random and gives you absolutely no incentive to replay due to the impossible difficulty of playing higher levels without coordinated teammates and specialized cards. This is why it’s been so controversial. Having enough cards to actually build an interesting deck in the first place is what makes this system work.

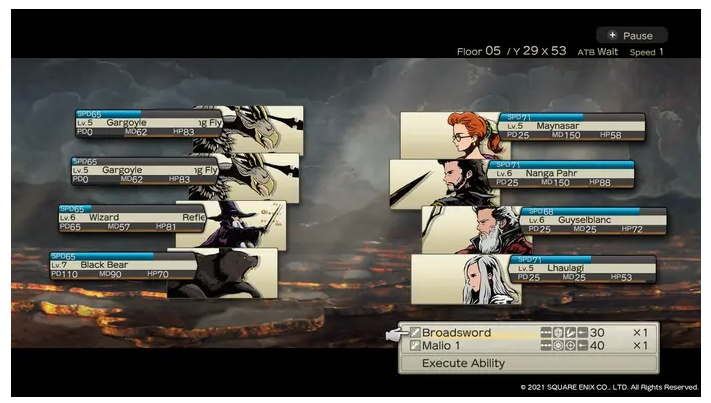

The game becomes much more rewarding if you don’t play alone and persevere through the relatively boring first stages as you progressively expand your collection of cards. It is possible to construct very specialized decks that drive you to the brink of “brokenness,” which is, let’s face it, the true appeal of any casual game with builds. I’ve only just begun to explore, but I’ve already seen some games—meetee in particular—that go completely bonkers, combining your character’s special abilities with stamina boosts, speed increases, and team-wide painkilling whenever you slay a zombie (which you will probably do a thousand times on harder difficulties).

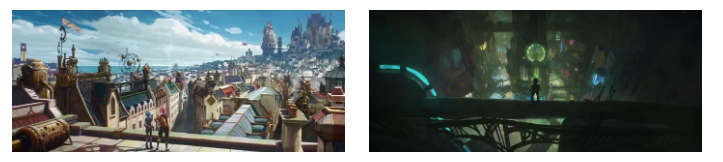

All of this is combined with sometimes really entertaining level design that aims for the heightened delight that every respectable zombie game should ideally embody. In one particularly hectic, tower-defense-style level early in the campaign, you have to hold out in a bar full of necessities, like barbed wire, molotov cocktails, and tons of ammunition, all while blasting punk-pop songs from a jukebox that you have to keep safe from zombies’ constant attention. This is done to divert a massive horde. One culminates in an upward “gauntlet” through a residential neighborhood, with many adversaries hurling themselves over the once beautiful picket fences on each side of you. In another, you have to climb up a mine where the objects simply fall from the roof. It’s just an absolute joy to go through these to the saferoom, laughing hysterically over the microphone while covered in guts, mud, and other unimaginable muck. You could also be spraying wildly with a modified LMG in your hands and a cheeky little machine pistol in reserve.

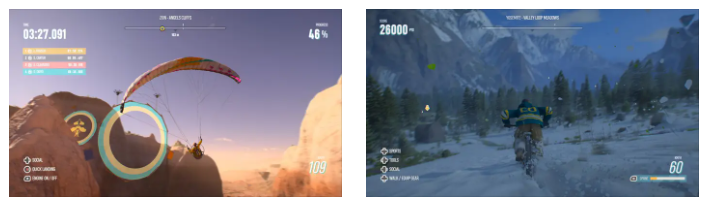

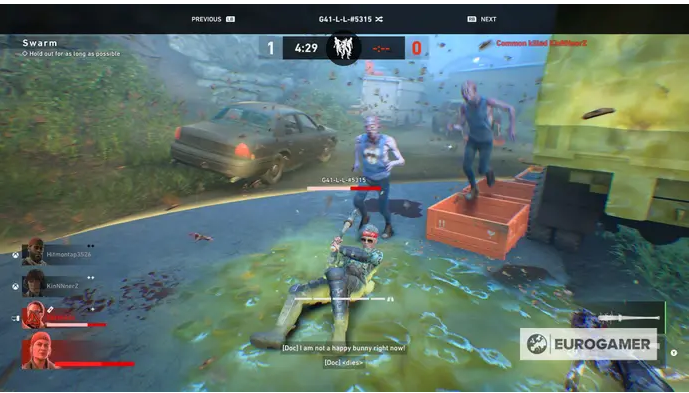

This also applies to a large portion of the shorter, maybe even more informal PvP mode. I had forgotten how awesome this was in the first Left 4 Dead games—a feet-up, half-awake, guffawing mode that was flawlessly timed for the hours of 12 to 4am. It functions essentially the same as the originals: you play as a team of humans against a team of zombies, then you switch roles. The only differences are the minor adjustments made to the levels, so it’s not so much a game of cat and mouse as it is a desperate attempt to escape as long as you can against the horde or a hectic dash for your life as a deadly bubble of insects (or whatever) encircles you.

It also helps that there are a few more opponent kinds in both PvP and the storyline. The three main types of zombies are: a large, “tall boy” type that can withstand a lot of damage and strike you with a large arm; a sneaky, nimble type that spits, jumps, and grabs; and a gigantic, exploding type that can attack you from a distance or approach you and blow itself up (don’t call it a “boomer” to avoid the lawyers getting upset). Although they do grow a bit monotonous in the campaign, each of those three subclasses—tall lads who grab, not-boomers who remain at a distant distance, and so forth—makes for enough variation to keep things interesting in PvP.

Really, it is the primary problem. There is a certain amount of repetition, and certain opponent designs aren’t as well done as the others. For example, most bosses lack inspiration; they are just Big Zombie monsters who squish bullets and push you about a little. Furthermore, I’m not a huge fan of the horde deck concept as a whole. Occasionally, it unleashes an improved version of mayhem or one of the more intriguing bosses (there’s an utterly repulsive “thing” known as a Hag that charges at you from afar, snapping up a comrade via a face-hole that resembles a worm before sinking into the earth). Its tiny little T-Rex limbs and terrifying theme tune provide it a great change of pace from the typical big boy opponents. At other times, however, the combination turns the levels into a true dirge.

Additionally, this may terribly tamper with the cards. The whole idea of that system is that you plan ahead. However, when you find yourself in a level, even with your powerful, chaotic LMG build, full of alarm-like zombies that, when triggered, summon a wave of enemies, all of the lights are out, all of the doors are alarming, and all of the enemies are tougher than before and require multiple powerful hits to take down, you may find that the enemy deck is forcing you to play stealthily. A good LMG could also be absent for a time since, except from the two that are also randomly generated and can be purchased at the beginning of each level with run-specific cash, all weapons are randomly generated. (And maybe your weird stranger buddy is really a bit of a zombie themself, charging into those alarming doors with the rest of your squad almost out of gas, but don’t even get me started.)

All of that is unfortunate, and it goes hand in hand with an overall feeling of clumsiness in certain areas. Take the peculiarity of having a sort of “hub,” which is utterly unnecessary and very 2015: a location where you can move around and physically interact with NPCs to get three words before accessing a menu that you can already access by opening the menu. Speaking of NPCs, the plot of the game appears to have completely vanished. It appears that some military guy is the one who introduces them, and everyone else fumbles around trying to buy new weapons before you begin a round. Eventually, you just start to notice the occasional non-sequitur about blowing up a bridge or saving a guy, and then you just tune out.

Luckily, however, neither I nor I imagine anybody else plays horde-based zombie shooters for their compelling story. Even though it’s a blunt instrument, you may cope with a poor roll on the level-modifier dice by simply ending the current run and beginning a new one if you’re at the beginning of one. Beyond that irritation, the user experience aspect of the game is really great. This includes cross-progression, cross-platform play, and chapters that, upon finishing a run, let you dash out to the hub-slash-menu to unlock a few more cards and adjust your decks before moving on. In essence, the entire experience is similar to a roguelite with checkpoints.

Basically, it’s practically there. Nearly really unique. Although it falls short of that, Back 4 Blood is still an amazing, untidy delight of a game. That’s quite an accomplishment as well, given that it achieved this by successfully putting a progression system on a beloved, cult favorite series that is best characterized as the video game equivalent of a bong.