The Analogue Pocket, which can play a variety of handheld cartridge games, including the whole Game Boy Catalogue and Sega’s Game Gear, is the closest thing we have yet to the ultimate retro portable. This enormously sized, exquisitely designed gadget runs on an FPGA processor. Imagine this as a chip that can be reprogrammed to match the hardware’s real logic, providing an almost exact replica of the functionality of the vintage consoles. That’s the idea, but does the Analogue Pocket live up to the hype? Analogue provided us with a black review device, dock, and related accessories for our evaluation.

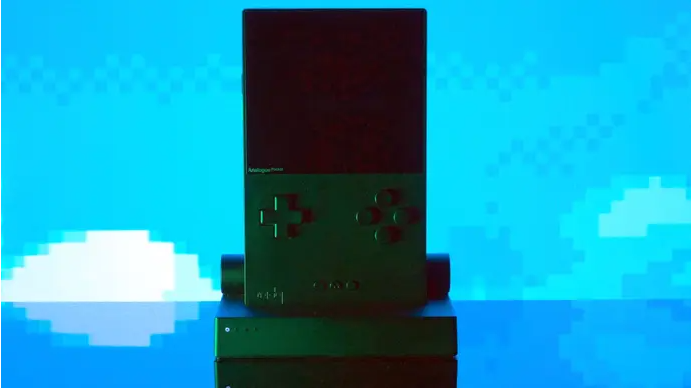

The Analogue Pocket is indeed a gorgeous gadget; its clean lines, delicately rounded edges, and gorgeous Gorilla Glass screen glass dazzle when you first take it up. You’ll be holding the Pocket in your hands most of the time, unlike, say, the Mega Sg, so it feels immediately premium in a manner that surpasses anything Analogue has done before. The device has a sturdy but manageably light feel to it. The face buttons are arranged in the classic diamond pattern, and the start and choose buttons are positioned close to the bottom, overlapping the menu button, which serves many purposes in this instance.

Because it’s so important to the way the system feels, the d-pad is never easy to use. This time, it works quite well. It’s marginally superior, in my opinion, than the d-pad features on a modified Game Boy. Similar to similar systems, diagonals, however, may sometimes cause issues in certain games, but overall, they work well. Two shoulder buttons for Game Boy Advance games and a somewhat exposed cartridge slot are located around the rear. This is an intriguing design decision since it implies that carts would sway in the absence of the extra support brace provided by the original hardware, but it’s surprisingly sturdy and allows you to see the lovely label artwork that adorns many titles.

It takes Game Boy, Game Boy Color, and Game Boy Advance cartridges by default. As of the time of this review, there is also a Sega Game Gear converter available, with compatibility for the Neo Geo Pocket Color, Atari Lynx, and more coming up in the next year. In addition to having a micro-SD card slot, a 3.5mm minijack output for headphones, and a Game Boy-style link-cable connection that lets you play multiplayer games even with original Game Boy Color and Advance hardware, the device charges via USB-C.

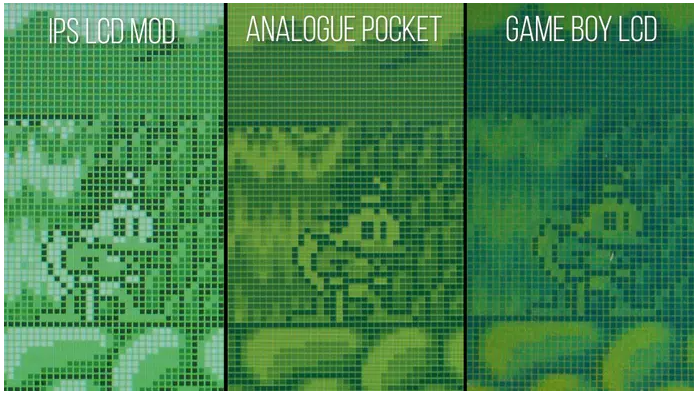

The screen and the different screen simulation modes are the primary and most significant features, but in order to fully comprehend this, we must first have a look at the original hardware. A spaced grid divides each pixel on the 160×144 screen used in the original Game Boy, creating an unusual design. It’s a very distinctive appearance, and similar features also apply to other portable systems. The reason this is significant is because the artwork in these games was made especially for these original panel and resolution sizes. Expanded inside an emulator or shown on a screen with a greater resolution, the result is an unsatisfactory visual and tactile experience.

To combat this, modders have created alternatives for LCDs that mimic the white space between pixels. This is frequently referred to as the “retro pixel grid.” Although they seem great, the style isn’t quite there. All of this creates a dilemma: the original displays on earlier handhelds are often of low quality, and although we want to mimic the color and pixel structure reproduction, we also don’t want to duplicate the ghosting or low visibility. And the Analogue Pocket has screen options that replicate the original displays’ appearance. For instance, the Game Boy has both faint color information inside the pixels and a visible border between them, which is intended to more precisely mimic the physical features of a genuine Game Boy screen. This one differs in that it is completely lighted and doesn’t show significant motion blur. You may also choose between different modes, one of which mimics the appearance of an indiglo screen from a Game Boy Light.

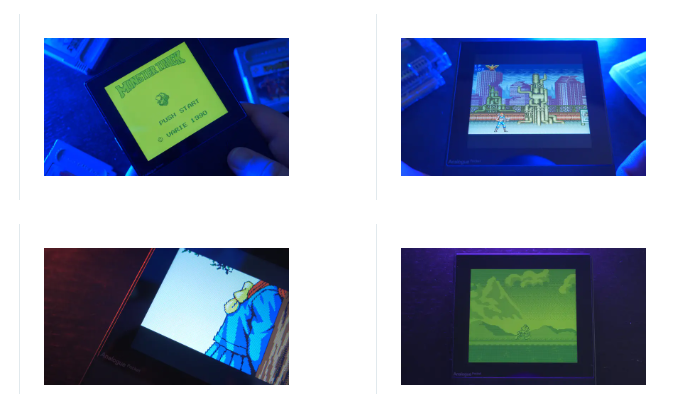

To be honest, the filter used for Sega’s Game Gear is perhaps the most amazing; this is a complex system that, in my opinion, is not often reproduced adequately via emulation or replacement displays. Similar to the Game Boy, the resolution is 160×144, but the pixels are bigger due to the greater aspect ratio. These days, it’s quite hard to view and utilize the original displays, and none of the replacement screens have this arrangement, thus scaling problems arise. Other countries’ Game Gear game releases likewise often fall short. On the other hand, the Analogue Pocket offers a very faithful Game Gear experience without any of the original panel’s shortcomings. It’s very amazing to see.

When it comes to emulating the pixels of the system and adjusting the color saturation to fit the content, the Game Boy Color screen emulation also seems fantastic in action. Nintendo Game Boy Advance? It’s more difficult with this one since the original hardware doesn’t adjust to the Pocket’s native 1600×1440 screen evenly, which causes certain repeated patterns to show on solid colors. Overall, I wouldn’t say it’s a big deal or a problem for most games, but it’s not nearly as good as the other systems. I’m not a big fan of this particular mode, which presents more like a standard emulator than a faithful recreation of the original display. However, there is an alternate option: an Analogue mode, which essentially displays the game in a raw pixel mode and opens up a number of additional scaling options.

The Pocket’s very high-resolution LTPS panel, which has 615 pixels per inch, accounts for the screen’s excellent performance. When it comes to producing LCDs, LTPS technology is the best available since it is effective, enables tightly packed pixel grids, offers quicker motion response, and creates deeper black depths. The main selling point of this product is that Analogue chose a premium screen with a desired aspect ratio, which sets it apart from many other portable gaming devices on the market today. There are more than enough pixels to replicate the features of individual pixels, as those in the Game Boy, because of the high resolution. Additionally, it enables a perfect 10x scaling, where 160 becomes 1600 and 144 becomes 1440. As a result, the screen measures 1600 by 1440. Additionally, the experience may be optimized by modifying the sharpness and saturation, which is crucial since the original panels were never able to show very rich colors.

Other interesting features include the frame blending tool. This is used when there is flicker rather than just adding fake ghosting to the mixture. Yes, the original Game Boy developers took use of the display’s flaws to create some very cool effects. Content that flickers quickly on a panel known for its LCD ghosting might mimic transparency, which is great for effects like clouds, water, and other effects. This flicker is caused by the quicker panel responsiveness when frame blending is deactivated. If you activate it, however, the system combines these two frames into a solid object while maintaining the desired effect.

In the end, the Pocket’s screen is superb. The quality of this panel is unmatched by any other clone device or aftermarket screen conversion, and in my opinion, it’s an example of what can be achieved when a sizable budget is allocated for a product of this kind and authenticity is the primary focus. Although finding a screen similar to the one used in the Pocket may be costly and challenging, I believe that’s a major component of the experience. The majority of screen modifications and emulation-based handhelds are restricted by screen choices. Is it flawless? Not exactly. Even though LCD technology has advanced much beyond its basic hardware, sample and hold LCD technology still has restrictions that lead to certain artifacts.

In addition to its high-quality screen, the Pocket boasts stereo speakers integrated into its sides, which can be adjusted to an unexpectedly loud volume. Better sound quality than any of the original systems is made possible by the speakers. But what I really want to talk about is the Game Boy Advance’s improved audio function. You see, I feel that sample-based playback causes the audio in Game Boy Advance games to sound choppy by default. This is essentially resolved by the better quality option here, which applies filters in a manner that greatly improves audio quality.

The sleep mode is the last significant hardware feature that is worth mentioning. When you press the green button while the Pocket is playing, your progress is preserved and it goes to sleep. Why does this matter so much? Simply said, it functions differently from the traditional consoles in that it may use original cartridges. It’s very amazing that this works as well as it does since the Pocket utilizes a live cartridge bus, which acts a lot like the actual thing. There is a catch, though: it is only compatible with genuine carts. Currently, the Everdrive (a cart replacement that uses an SD card to execute ROMs) does not support sleep mode and will prompt you to shut down instead.

Although this function is still in development, it is also possible to create actual save states. However, these states are just temporary and vanish when you switch games. Analogue says that when Analogue OS gets its significant upgrade, more comprehensive support will be available. However, there is a great deal of extra convenience here while playing portable games between this and sleep mode.

Therefore, the Analogue Pocket is a hardware home run. However, I should briefly discuss battery life. I don’t believe there will be many issues with this. The Pocket has a 4300mAh lithium-ion battery, and I was able to shoot a full day’s worth of b-roll footage on only one charge. Nevertheless, the Pocket may also be used with an external monitor, in which case the Dock is useful. With two USB-A connections, a USB-C port for power, and an HDMI output, this is a robust gadget. To play on your TV, just slide the Pocket into the socket. Even if the hardware has been fixed as of right now, the experience is still far from over. Although the Dock is now rudimentary, Analogue informs us that many more functions, such as the ability to utilize Analogue’s DAC for use with CRT screens, would be included in a forthcoming firmware update. This is something I myself look forward to.

First off, there aren’t many settings for the display itself; none of the more sophisticated screen configurations from portable mode work when the device is docked. I wouldn’t expect them to be able to replicate this exactly since there are less available pixels for 480p, 720p, and 1080p output, but I would want to see this improved as Game Boy games in particular significantly benefit from this. Instead, there aren’t as many palette selections as I had hoped for, but they’re still excellent on their own with nice colors. It’s closer to what you would get from a Game Boy Player or Super Game Boy, for example.

This also applies to other aspects like color saturation, which is unavailable in docked mode. For systems that have color displays in particular, this implies that the TV output will provide excessively saturated colors that lack authenticity. Then there are the choices for scalability. When playing handheld, scaling is not possible if you are using any of the pixel modes; the choices are grayed out. Therefore, before docking it, you must first switch to the default display mode. You may then manually resize the picture to your preferred size. Additionally, you can attach Bluetooth controllers with the dock, such the Switch Pro or PS4 controller, or those from 8bitdo. However, in the end, it seems like the Dock isn’t as effective or well-thought-out as the device itself, while being handy. It’s essentially a work-in-progress that needs important feature improvements to really shine.

It’s all about the FPGA cores’ precision, not the technology. Although the Analogue Pocket was the first handheld with a fully integrated FPGA, this does not imply that the original hardware has been perfectly recreated. This kind of gadget is tested by examining how the hardware duplicates edge cases, or games that push the technology in novel ways that may cause FPGA cores and incorrect emulators to malfunction. Although it is not possible to test every game for a review here, the fact that it can run these troublesome games is a positive indicator of accuracy.

The video at the top of this page has my whole test suite. Suffice it to say, the Pocket is almost flawless and even works nicely with state-of-the-art scene demonstrations. The only homebrew DX adaptations that performed poorly on the Pocket using an Everdrive were Super Mario Land 2 and Metroid II, which had issues with tile color. Nevertheless, noticeable errors also exist on actual hardware; they simply manifest in various ways. Overall, this has excellent accuracy and compatibility.

Concluding, the Analogue Pocket really is the genuine thing. I’ve evaluated and used a variety of contemporary vintage gaming equipment, such as FPGA-powered hardware, software emulators, and original console modifications. My new go-to device for playing the whole Game Boy and Game Gear library is the Analogue Pocket. Really, there isn’t anything better available at the moment.

And what about the times ahead? The OS still lacks important functions, which should be added sometime in the next year. Since the console has a second FPGA chip, these capabilities have the potential to be very intriguing and game-changing since they let developers design new cores for other systems. Better dock support and more adapters are also on the horizon. Nevertheless, the Pocket remains an incredible accomplishment even in the absence of these functionalities. It’s precisely what I’ve been waiting years for, particularly in terms of screen quality, where other systems and modifications fall well short. For a project of this caliber, the cost is also quite fair: shipping is $219, and pre-orders are being accepted again today.